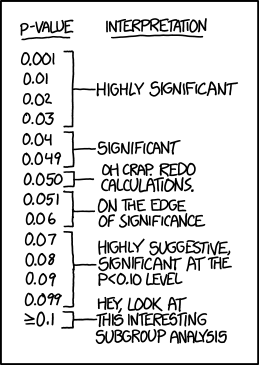

Randall Munroe takes a poke at over-valuers of p in this XKCD cartoon

Nature weighed in with their shots against scientists who misuse P values in this February 2014 article by statistics professor Regina Nuzzo. She bemoans the data dredgers who come up with attention-getting counterintuitive results using the widely-accepted 0.05 P filter on long-shot hypotheses. A prime example is the finding by three University of Virginia finding that moderates literally perceived the shades of gray more accurately than extremists on the left and right (P=0.01). As they admirably admitted in this follow up report on Restructuring Incentives and Practices to Promote Truth Over Publishability, this controversial effect evaporated upon replication. This chart on probable cause reveals that these significance chasers produce results with a false-positive rate of near 90%!

Nuzzo lays out a number of proposals to put a damper on overly-confident reports on purported scientific studies. I like the preregistered replication standard developed by Andrew Gelman of Columbia University, which he noted in this article on The Statistical Crisis in Science in the November-December issue of American Scientist. This leaves scientists free to pursue potential breakthroughs at early stages when data remain sketchy, while subjecting them to rigorous standards further on—prior to publication.

“The irony is that when UK statistician Ronald Fisher introduced the P value in the 1920s, he did not mean it to be a definitive test. He intended it simply as an informal way to judge whether evidence was significant in the old-fashioned sense: worthy of a second look.”